|

| Carlton E. Morse |

Unfortunately there was no way to get any more information since Chris passed away a number of years ago. If my memory serves me correctly, the details are more intriguing. If I recall accurately, Chris had acquired a copy but apologized in person to the fan club. It seems someone broke into his house and stole the only print of the 25-minute TV pilot. It was never screened and the fans spent the night watching all three Columbia pictures and the Batman-camp-style made-for-TV pilot movie with Ida Lupino.

Flash forward a couple years. Browsing the Ziv-TV archives with the assistance of John Ruklick, I mentioned the unsold pilot to John and asked him to copy whatever he finds about I Love A Mystery, provided there is something. Everything was filed away alphabetically and following I Led Three Lives was nothing. But persistence pays off because looking over everything, following the letter Z was one file all by itself. It was labeled, "I Love A Mystery." ZIV really did produce a pilot of the same name! Sadly, the shooting script was not available in the archive. And imagine my disappointment when I discovered that the proposed series was not based on the I Love A Mystery radio program, created and written by Carlton E. Morse. It was nothing more than an anthology of mystery stories.

There is a shining light at the end of the tunnel. Recently, Brendan came across an oddity on eBay and brought it to my attention. "On eBay a good while ago there was a fellow selling a letter that was from Dick Powell (representing Four Star) looking into the rights to the show," he explained. "The weird thing was that the actual reproduction of the letter was not coming up. It was a picture of something else. I emailed the seller and asked exactly what the letter entailed and explained that the reason I was asking was because a photo of a different item was coming up. He answered that he would correct the error, but he never did. He just took the listing off. I contacted him again about this letter but he never got back to me." This comes as no surprise to me. In 1961, Broadcasting magazine reported that Four Star had secured the television rights to The Adventures of Sam Spade, another popular radio mystery, and that filming has recently been completed with Peter Falk in the title role. To date, neither the Sam Spade or the I Love A Mystery pilots produced by Four Star have surfaced for collectors and fans of the program. That is, if ILAM was truly produced by Four Star.

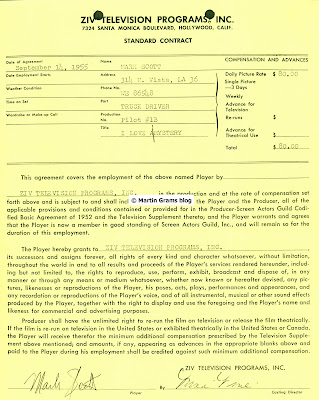

So for all you die-hards who are curious to look over the production paperwork, the following might be of interest so I am reprinting them below (with some explanation).

|

| Inter-office memo dated September 12, 1955 |

Inter-office memos like this one often reveal juicy details of what was going on behind the scenes. While pursuing the Warner Brothers television files, for example, I discovered that Ty Hardin (Bronco) was showing up at the set not knowing his lines and this was pre-empting production. It seems a number of directors had complained and the inter-office memo revealed the studio heads' various options at how to approach the actor.

Another inter-office memo between executives at NBC (East Coast and West Coast) asked that each other keep tabs on a certain radio celebrity because, as they mildly put it, "is one of the slickest operators we have." Seems when the show was making the move from one coast to another, they wanted to make sure he wasn't going to try pulling off the same stunts he already accomplished.

A recent trip to the Library of Congress with my good friend Neal Ellis revealed an inter-office memo about Ed Wynn being reprimanded for leaving cigarette butts in the studio! This inter-office memo also reveals the official name of the company, Ziv Television Programs, Inc., evident by the letterhead. The memo was also carbon copied to William Castle, the director, so he was made aware that Sidney Blackmer's participation had to be limited to one day (which meant no retakes or staggering behind in production).

|

| Operation Sheet |

For those who are not aware, television production from the fifties and sixties did not extensively credit every person involved. Unless they were a member of a union or guild, in which their contracts stipulate on-screen credit, or they played a major part of production, the crew (regular or irregular) were not usually credited on the screen.

Operation sheets were drafted for every television production, revealing who exactly was involved with the production. The first assistant cameraman (Dave Curlin), the assistant prop man (Robert Murdock), the electricians (Charles Stockwell, Charles Hanger, Harold Kraus, Richard Brightmier and E. Newbaur), and the recorder (Ken Corson) were among the handful of people who were never credited during the closing credits.

I do want to apologize in advance for the scans. Most of the production sheets were on legal paper, not letter. My scanner is not long enough to scan them in their entirety, so I was forced to cut off the bottom inch or two of each scan.

Hence, "Operation Sheet" (with the caption below it) is missing some of the details such as gaffer (Joe Wharton), set labor (Sol Inverso) and construction chief (Dee Bolhius). It should also be noted that production sheets were not always accurate when it came to the spelling of cast and crew. So if you ever consult such sheets for your write-up, I suggest you double check the spelling of the names. Sometimes this can be very difficult when the last name is spelled two different ways in the closing credits of the same series (I've come across that before)!

The first sheet reveals, as you can see, the exact days of filming. In this case, September 15, 16 and 17, 1955. While the name of the series is I Love A Mystery, the name of the actual drama is "I Owe You." Obviously, the next episode would have had a different title (such as.... "The Case of the Queer Poison). You might have also observed the type of film they used, 35mm, which was standard in TV production.

Also note that the episode was filmed in black and white. This is a clear indication that the pilot was not filmed in color. Way too many times I have read where a program or specific episode was supposed to be in color and those ignorant of the facts, hurt themselves by not buying a commercial DVD when they believe there is a better print elsewhere. For years I had a copy of a television pilot for The Phantom, with Lon Chaney Jr. and Paulette Goddard, in black and white. Boy, was I surprised when someone turned up a 16mm print in color!

For ZIV Television, this can be confusing. All of The Cisco Kid television episodes were filmed in color. Yet, black and white prints exist in collector circles. For I Led Three Lives, which ran three seasons, only season two was filmed in color. This confuses fans who "believe" that all three seasons were shot in color.

For Science Fiction Theatre, Ziv shot the first season in color and the second season in black and white. Why? Because enough stations renewed the series for a second season, but not enough to warrant the additional expense, so Ziv agreed with producer Ivan Tors that he could have a second season if he was willing to have the series filmed in black an white. Tors agreed. So the belief that every episode of any particular series was shot solely in one format needs not apply. (Heck, remember F-Troop? The first season was shot in black and white and the second season was shot in color.)

The last Operation Sheet reveals how many extras and standins were available during filming, and exactly which day or days each actor was needed for filming. Most of us know that television episodes are never filmed in sequential order. Scene 24 can be filmed before Scene 3, to accommodate for the actors' schedules.

Daily Production Sheets are commonly found for each and every television episode. Since the entire production was filmed in a studio and not on location, the first sheet (dated Wednesday, September 14, 1955) reveals the exterior of the roadside diner was constructed inside. The word "format" on the top right and the narrator, Paul Kelley, used for the opening voice over narration, means that production on this evening was for the title sequence, which would have been used for each and every episode of the series.

Recognizing the emerging importance of television, in 1950 Ziv signed a five-year $100,000 lease with California Studios in Hollywood to produce television programming. By 1952 Ziv Television Programs Inc. had nine series available for syndication including Sports Album and Yesterday’s Newsreel as well The Cisco Kid, Boston Blackie, The Unexpected, The Living Book, and Story Theatre.

Ziv also offered a package of feature films reportedly leased from distributor Budd Rogers, and a cartoon package leased from Walter Lantz. Realizing that the company was truly in the television production business, Ziv purchased American National Studios (formerly Eagle- Lion Pathé Studio) on Santa Monica Boulevard in late December 1954 for a reported $1.7 million. I mention this because you'll notice that American National Studio was listed on the Daily Production Sheet.

Howard Duff and Maria Riva carried most of the scenes on I Love A Mystery, as evident not only because they were among the cast for all three days of production, but the only actors required for the first day of filming.

Notice how the studio kept track of when the actors appeared for hair and makeup, how long their lunch breaks are, and number of film produced including "negative waste."

Keeping tabs of how much film was put into the can, by the day, was very important. This let the studio know if they were falling behind or ahead on schedule.

On the final Daily Production Sheet, you'll notice the notation that the camera crew was dismissed at 6 p.m., but sound continued until 6:15. That means one of the actors, Dennis King Jr. (as you can see on the "Time In Studio") was providing his voice for an audio recording to be played on the program (the voice on the other end of the telephone).

Such notations are not uncommon and often reveal who tore their pants on the set, when a battery backup went dead while filming on location, and other factors that explained why a brief delay in production.

Ziv dominated the field. Of the six distributor categories in Billboard’s fourth annual TV film service awards, ZIV-TV won first place in four and was second in one. As far as the poll was concerned, ZIV-TV in 1955 (the same year this pilot was made) maintained its leadership in TV film syndication. The company’s status in the Billboard polls remained constant through most of the 1950s in the same manner.

No one knows why I Love A Mystery never sold. Historians only speculate that the title of the program might have been a conflict with the Carlton E. Morse program, but that is only speculation. “Most of our shows were not offered to the network,” Ziv recalled to interviewer Irv Broughton. “A program like Sea Hunt, for example, was turned down by the network. We showed it to each of the networks, showed them the pilot. They liked the pilot, but they figured—and each one seemed to be of the same opinion—‘Well, what do you do the second week and what do you do the third week—you’ve done it all the first week.’ Well, of course, they were wrong; we produced it year after year.”

The Cast Sheet reveals which actors played what fictitious roles, the name of the actors' agents, and phone numbers for both actors and agents. The Breakdown sheets reveal which scenes in the script were filmed (in which order), and props used on the set.

While most major film studios operated five days a week, ZIV Television worked six days a week excluding Sundays—unusual for television production during the fifties. “Filmmaking was fun, but it was also hard to be a Latter-day Saint and work in the picture business during Hollywood’s heyday,” recalled director Henry Kesler. “The system itself worked to make it difficult to observe church teachings.”

“The folks at ZIV were more concerned with budget than our creative talents,” recalled director Leon Benson for a trade column in the early seventies. “I often felt the pressures when something went wrong. They passed around an internal memo one afternoon reminding those of us underpaid that each television production was to be completed within two shooting days. The next day a power outage put us a full hour behind schedule one morning and I was sweating every minute we waited for the power to return to the set.”

Howard Duff, by the way, had worked with Ziv Television before. In March of 1955, six months prior to filming this pilot, Duff made a guest appearance for Science Fiction Theatre. The episode was titled "Sound of Murder." During a top-secret conclave of scientists in Washington, one of the group, Dr. Kerwin, receives a phone message from his superior, Dr. Tom Mathews (Duff), to meet him in a certain hotel room.

Kerwin is later discovered murdered, and key papers concerning a top-secret project are missing. Mathews is arrested both because of the phone call and more importantly because he had disappeared for six hours that evening, deliberately losing an FBI agent assigned to guard him. Tom’s only explanation is that he went for a walk. But the ensuing Justice Department investigation turns up a number of phone calls which Mathews allegedly made to the other scientists on the project, in each case requesting secret information. Mathews is indicted, regardless of how much he claims innocence. His case seems hopeless, until Mathews and a scientist friend mathematically figures out how the phone calls were made, and how not only his voice was duplicated, but also his knowledge of the workings of the project, through the use of an intricate instrument called a “Sound Synthesizer,” used to replicate another man’s voice and calculates an answer to a question by the recipient. By this means they trap the real murderer and traitor.

What you will find below the Breakdown Sheets are the Standard Contracts for each and every actor who appeared in the pilot. Like the Operation Sheets and the Daily Production Reports, I did not scan the very bottom of each contract, because the actors' social security numbers were listed and for obvious reasons, I do not feel that providing such social security numbers would be appropriate.

In closing, while I found a copy of the unaired I Love A Mystery pilot, it is in the original 35mm format and I have no means of having it transferred to DVD. There is (as described above) proof that there is at least one 16mm master available in collector hands.

Update August 8, 2014: This blog post was originally published in July of 2011 and a private collector read it and discovered what they had was a Holy Grail for TV and OTR fans. He since contacted me and a few days ago the 16mm print arrived at my front door, courtesy of UPS. Working on having it transferred to DVD and with luck, it will be screened at this year's Mid-Atlantic Nostalgia Convention in September.

Update August 8, 2014: This blog post was originally published in July of 2011 and a private collector read it and discovered what they had was a Holy Grail for TV and OTR fans. He since contacted me and a few days ago the 16mm print arrived at my front door, courtesy of UPS. Working on having it transferred to DVD and with luck, it will be screened at this year's Mid-Atlantic Nostalgia Convention in September.